The Trial

Sudden cardiac arrest is the leading cause of death in otherwise healthy adults affecting ~25,000 Australians per year, with death occurring in 87-94% of OHCA cases. Extracorporeal life support is a form of peripheral heart bypass and it can be used in the setting of cardiac arrest (ECPR). While the heart is arrested, the machine provides oxygenated blood to the brain, heart and other vital organs, essentially stopping the clock and buying time for the cause of the arrest to be treated and for the heart to recover.

When the heart is in cardiac arrest and no CPR is being performed, this is called a ‘no-flow’ state. When CPR is commenced, this is termed a ‘low-flow’ state. This low flow decreases over time. Good (oxygenated blood) flow is needed to maintain perfusion to the brain, heart and other vital organs. ECPR provides excellent blood flow during cardiac arrest.

ECPR has been used in the hospital setting for some time and has improved cardiac arrest survival rate in the refractory VF population from <5% to 20-33%. One of the key determinants of outcome in this patient population is the duration of the cardiac arrest, that is, how quickly the patient is established onto extracorporeal support. With appropriate patient selection, the quicker the patient is placed onto extracorporeal support, the better the outcome.

PRECARE is a study examining the feasibility of performing ECPR in the pre-hospital setting, with the aim to reduce the low flow time and improve survival rates whilst also improving equity of access to this therapy. Phase 1 of the PRECARE study has been running for 6 months and is complete. Phase 2 of the trial is now commencing. Westmead, Royal Prince Alfred and St Vincent’s are the sites accepting patients for this study. The study is currently run over 3 days: Monday, Thursday and Friday.

ECPR will not work without effective and immediate bystander CPR and the provision of excellent advanced life support, it is a team sport. Advanced principals and invasive techniques as adjuncts to advanced life support (ALS) In addition to providing ECPR to eligible patients, the PRECARE medical team also offer advanced, traditionally hospital based interventions, in the pre-hospital setting. The team consist of two consultant doctors and one critical care paramedic. This team are essentially bringing hospital based interventions to the patient. These interventions do not detract or replace paramedic resuscitation, rather they enhance the advanced life support being provided by paramedics.

Insertion of a femoral arterial line to monitor central perfusion pressure, effectiveness of CPR and titration of inotropic support to improve coronary perfusion. Transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) to determine optimal compression placement, ensure optimal forward flow with CPR delivery, assess for reversible causes and guide treatment. Real time arterial blood gas analysis to assist with decision making and treatment strategies

While we know that perfusion and oxygenation are the main stays of cardiac arrest management, what we are learning is that there are various cardiac arrest phenotypes and not all cardiac arrests are created equal. To improve survival from cardiac arrest, we need consider tailoring management to the individual patient. Consider heart lung interactions, patient anatomy and pathology impacting on arrest physiology because we are learning that personalised haemodynamic directed CPR can improve outcome.

Research Protocol

Rationale

Conventional treatment of out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA), focusses on chest compressions and defibrillation but even with conventional CPR, survival decreases quickly. Return of spontaneous circulation or (ROSC), where the heart starts beating again, occurs in approximately 33% of OHCAs in Australia(2) and 95% of these get ROSC in the first 15 minutes of CCPR.(3) After 15 minutes of CCPR the arrest is deemed “refractory” and the probability of good functional recovery falls to ≈ 2%(3) and at 30 minutes <1% of patients survive.(4) Up until recently, the treatment in prolonged OHCA where ROSC does not occur quickly, was limited to continued conventional resuscitation at scene (i.e., more of the same treatment).

Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in OHCA

Whilst conventional resuscitation provides some blood flow to the brain and vital organs, this is less than one third of normal cardiac output and is not enough to sustain the body. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is circulatory support technology that enables full blood flow to a patient’s vital organs and is used in a number of hospitals across Australia. When ECMO is implemented during a cardiac arrest it is termed – Extracorporeal CardioPulmonary Resuscitation or ECPR. ECPR is almost universally implemented after the patient has been transported from the scene of OHCA back to selected hospitals (hospital-based ECPR). Many non-randomised studies of hospital-based ECPR,(5, 6) including our own retrospective(7) and prospective experience,(8, 9) report survival rates well above comparable refractory OHCA treated with CCPR.

The challenges of hospital based ECPR

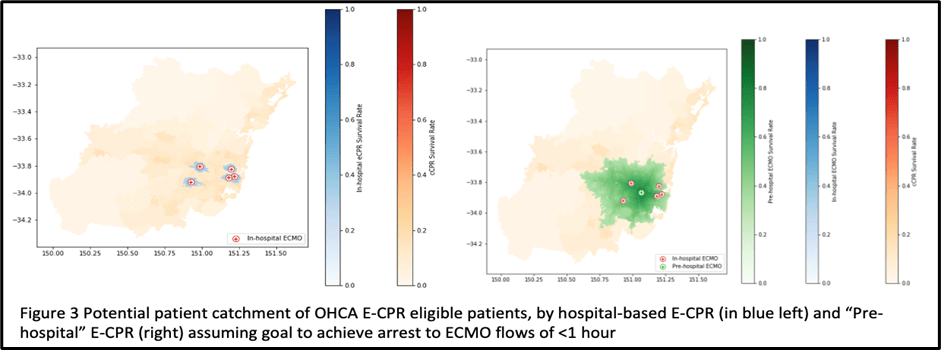

It is recommended that in ECPR, ECMO flow is commenced within 1 hour of cardiac arrest.(12) Earlier implementation of ECMO flow is associated with even higher survival rates when compared to conventional CPR – speed to implementation of ECMO flow is paramount. Owing to the resources and the technical skills required, ECPR is only offered at a small number of metropolitan hospitals. This significantly limits access. Given the time taken from 000 call to arrival at the patient, resuscitation attempt, then extrication and transport of the patient to hospital, it is extremely challenging for potential ECPR patients to arrive at an ECPR capable hospital in <1 hour.

The 60-minute cut off reduces the geographical area and population that can be covered by hospital based ECPR. There is currently only a relatively small area of metropolitan Sydney hospitals (Figure 1) where patients can reasonably be expected to arrive within the time cut offs. Many other patients who meet ECPR criteria outside of this area are ineligible, worsening inequality of healthcare access.

In addition to the difficulty in getting patients to hospital in less than 1 hour, transportation of a patient during CPR creates many challenges which can impair the quality of the CPR(16)

In summary, while existing data are supportive of the provision of hospital based ECPR over conventional CPR, in cities where transport times are routinely >60 minutes (8,9,10), there are significant challenges to the effective, equitable and efficient use of this technology.

PRIMARY STUDY OBJECTIVE: To assess the rate of neurologically intact survival to hospital discharge in adult patients (aged 18-70 years) with refractory OHCA treated with prehospital ECPR compared with those treated with conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CCPR) or in hospital ECPR.

STUDY DESIGN

A clinical observational cohort trial of pre-hospital ECPR with contemporaneous matched registry of conventionally treated OHCA as a comparator group. The comparator group will include otherwise eligible patients that fall outside the geographic bounds of the ECPR team.

Prior to commencement to the main PRECARE study a 6 month (estimated 10 patient) run in period will be completed.

INCLUSION CRITERIA

- Adults over 18 years of age and under 70 years of age

- Witnessed cardiac arrest where no flow times can be reliably ascertained and bystander CPR (no flow time < 5 min)

- Refractory cardiac arrest: the failure of medical professionals to obtain sustained return of spontaneous circulation at the 15th minute of cardiac arrest with a minimum of 3 external defibrillator if indicated

- Shockable initial rhythm, with End-Tidal CO2 (ETCO2) > 10 mmHg at the time of inclusion

- PEA initial rhythm, if: signs of life during resuscitation (spontaneous movement, absence of mydriasis and/or pupillary response, spontaneous breathing movements) and: End-Tidal CO2 (ETCO2) >10 mmHg at the time of inclusion

- Suspected medical cause of the cardiac arrest (excluding traumatic cardiac arrest)

- Drug overdoses with suspected cardiotoxic drugs

- Commencement of ECMO cannulation < 45min from time of cardiac arrest. or if >45min and <60min AND exhibiting signs of life during CPR

- cardiac arrest was witnessed and ‘no flow’ times can be reliably ascertained

EXCLUSION CRITERIA

- Initial rhythm asystole

- End-Tidal CO2 (ETCO2) < 10 mmHg at the time of inclusion

- pregnancy

- Duration > 5 minutes without cardiac massage after collapsing

- Co-morbidities that compromise the prognosis for short or medium-term survival

PARTICIPANT RECRUITMENT ENROLMENT

If a patient is in cardiac arrest, standard resuscitation as per the existing NSW Ambulance protocols will be performed by the responding paramedics. The pre-hospital ECPR team will assess for inclusion and exclusion criteria. If there is any uncertainty around these criterion, standard resuscitation protocols will be followed and pre-hospital ECPR will not be initiated. Assessment will be made as to the scene elements and feasibility of the procedure. A “STOP/GO” checklist will be completed whilst ongoing resuscitation is continued. If the patient meets criteria, and it is 20 minutes or more since the cardiac arrest and the ECPR team decision is to “GO”, the patient will be enrolled into the trial.